- Home

- Stuart E. Eizenstat

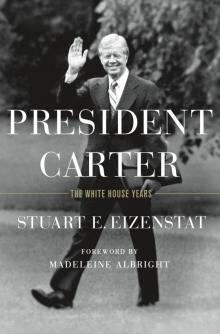

President Carter

President Carter Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Author

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

St. Martin’s Press ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on Stuart E. Eizenstat, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this ebook to you for your personal use only. You may not make this ebook publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this ebook you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To my wonderful loving wife, Fran, who, for forty-five years, including the challenging Carter White House years, was my selfless life partner, my closest adviser, and my most ardent supporter. She is deeply missed.

And to my parents, Leo and Sylvia, firstborn-generation Americans, who took great pride that their son could work in the White House.

It is not the critic who counts: not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles or where the doer of deeds could have done better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood, who strives valiantly, who errs and comes up short again and again, because there is no effort without shortcoming, but who knows the great enthusiasm, the great devotion, who spends himself for a worthy cause; who, at the best, knows, in the end, the triumph of high achievement, and who, at the worst, if he fails, at least he fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who knew neither victory nor defeat.

—THEODORE ROOSEVELT, “CITIZENSHIP IN A REPUBLIC,” SORBONNE, PARIS, APRIL 23, 1910

FOREWORD

I worked on the staff of Jimmy Carter’s National Security Council, and it was there that I first got to know Stuart Eizenstat. I have always admired his work ethic, his fine brain, and warm heart—qualities that mirrored those of our boss. I have also always counted on Stu to tackle challenges with unimpeachable integrity and complete honesty. That is precisely how he approached this book. Forty years after Carter’s inauguration, the time is ripe for a reappraisal of his presidency. No one could be better suited to undertake such a project. Stu helped lead Carter’s historic 1976 campaign and served with distinction as his chief domestic policy adviser in the White House.

He does not argue that Jimmy Carter was a perfect president, nor does he overlook the shortcomings and faults of our thirty-ninth president. But Stu makes a compelling case that Carter’s four years in the White House deserve far more credit than he generally receives. Those who dismiss Jimmy Carter’s considerable accomplishments as president are doing a disservice to the historical record, and to the country.

This is particularly true in the realm of foreign policy. President Carter was idealistic; he wanted America to present a morally untainted image to the world. His national security adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski, distrusted the Kremlin leaders and had no illusions about our struggle with the Soviet Union. But both agreed that we would be more successful in countering Communism if we made respect for human rights a fundamental tenet of our foreign policy and in our national interest.

Four months after taking office, Carter explained America’s new approach in a speech at Notre Dame, rejecting rigid moral maxims but declaring that the United States had so much faith in democratic methods that we should no longer have an “inordinate fear of Communism”; embrace dictators simply because they fought Communism; or “adopt the flawed and erroneous principles and tactics of our adversaries, sometimes abandoning our own values for theirs. We have fought fire with fire, never thinking that fire is better quenched with water. This approach failed, with Vietnam the best example of its intellectual and moral poverty.” President Carter’s commitment to human rights made me proud to serve in his administration. It also contributed mightily to the credibility of U.S. leadership and to the eventual expansion of democracy in Latin America, Asia, Africa, and Central Europe. By declaring America’s opposition to apartheid and brokering the historic Middle East Peace Accords at Camp David, Carter proved himself to be both a proactive and a principled president.

One foreign-policy accomplishment that remained elusive was a nuclear arms reduction agreement with the Soviet Union. As director of legislative relations for the National Security Council, I was deeply involved in the effort to obtain the Senate’s consent to the SALT II Treaty. We probably would have succeeded if on Christmas Day 1979 Soviet troops had not invaded Afghanistan. The Carter administration pushed back against this act of aggression economically by halting grain shipments and by banning the transfer of advanced technology. It responded politically by boycotting the Moscow Olympics and reinstating draft registration.

At the same time the administration’s attention was equally focused on Iran, where militants backed by a revolutionary Islamic regime seized our embassy and held our diplomats hostage. President Carter was consumed with saving their lives, but the public quickly grew disenchanted; the press was brutal in its focus on the hostages; and all this fed into a feeling of national helplessness that was soon exploited by Ronald Reagan. He proved a far more formidable adversary than many Democrats predicted, and in my eternal optimism I thought we could beat him. I was wrong.

Although the verdict of the voters was clear, history’s verdict on Carter is still being debated. He laid the foundations for conserving energy as a national policy and normalized relations with China. He poured out a cornucopia of good ideas, but they spilled out so swiftly and simultaneously that Carter obscured his own priorities, sending Congress more than it could handle, and foreign leaders and the American people more than they could absorb.

With the benefit of hindsight, public perceptions have begun to change, and with Stu Eizenstat’s important contribution, my hope is that those perceptions will continue to evolve so that Jimmy Carter will be recognized as the consequential and successful president that he was. I will always think of him as one of our most intelligent chief executives, who showed a fierce dedication to conflict prevention and individual human dignity, both during and after his term in office. He is a great man, and our country was lucky to have him as our leader.

—Madeleine Albright, former Secretary of State

PREFACE

I never expected to participate in Jimmy Carter’s 1970 run for governor of Georgia. But I had contracted an incurable political bug at the University of North Carolina, participating in student government, writing articles on policy issues for the student newspaper, hearing President Kennedy challenge my generation to public service at a 1962 speech in Kenan Memorial Stadium, and in 1963, undergoing a transformative experience serving as a congressional intern in Washington in a university-sponsored program. During the summer of 1964 I worked on the political staff of Postmaster General John Gronouski, the first Polish American in a presidential cabinet. Under the direction of Robert L. Hardesty, I drafted speeches for President Johnson’s election that were transliterated into phonetic Polish for him to wow his audiences with his nonexistent Polish skills. I did double duty working at the National Young Democrats of America. That earned me a trip to my first National Democratic Party Convention at Atlantic City, where my sole contribution was joining my fellow Young Democrats—at the instruction of Lyndon Johnson’s chief of staff, Marvin Watson—in occupying the seats of the Mississippi Democratic Party and, he emphasized, not leaving even to go to the bathroom until the Rules Committee decided whether to seat the all-w

hite or the racially mixed Mississippi delegation.

In the summer of my first year at Harvard Law School I made my first trip to Israel, to see my aging grandfather, Esor Eizenstat, who had emigrated (“made Aliyah”) in 1952 from Atlanta. In the summer of 1966, I worked in the civil rights division of the Office of Education at the then Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, volunteering at night in Head Start’s civil rights section. After graduating from Harvard Law School, I followed Hardesty to Johnson’s White House staff, drafting speeches for members of Congress—in English, this time—to support LBJ’s legislative initiatives, working on presidential messages to Congress, and attending congressional relations meetings at the White House. When LBJ occasionally appeared, with his massive size and fierce visage, it was like the Lord himself entreating everyone on an important vote. When Johnson pulled out of the 1968 race, I became the research director of Hubert Humphrey’s unsuccessful presidential campaign.

After his narrow loss, I returned home to Atlanta and made a beeline for the impressive law office of Carl Sanders, the prohibitive favorite for a new term as governor after sitting out for four years. He had been a successful, popular, moderate governor, with a formidable war chest and the backing of the press and the business and political establishment. He was handsome, well-tailored, and the epitome of what I expected from a senior partner at one of Atlanta’s most prestigious firms. After he left office, Sanders had turned his service in the State House into considerable wealth, and I offered to help his campaign, pointing to my work in Washington and my roots in Atlanta. He was a progressive on racial issues, at least by Georgia standards, and an owner of the Atlanta Hawks NBA basketball team, which I thought might help because I had been an All-City and Honorable Mention All-American basketball player at Atlanta’s Henry Grady High School (albeit with a large asterisk, playing in a segregated all-white league). Sanders seemed only mildly interested.

Shortly after that meeting, Henry Bauer, Jr., a high school friend, told me he was supporting someone he described in glowing terms as a bright, young, and very impressive former state senator from southwest Georgia, Jimmy Carter, who was taking Sanders on. I told Henry I had committed to Sanders, but he pestered me unmercifully, and so I met Carter at an office across from the federal courthouse, where I was serving as a law clerk to U.S. District Court Judge Newell Edenfield. What I saw was the polar opposite of Sanders and his sumptuously appointed law office: a small room with nothing but a folding table and lamp and two other pieces of furniture, one metal folding chair on which Carter sat, and a second for me. There were no suits, ties, or cuffs. Carter wore khaki pants and an open-collared tan shirt, with brown work boots. It did not take long to see what had drawn Henry to Carter.

He was slight in build and height, but he reminded me of JFK, with his handsome face, full head of sandy hair, and captivating smile. He told me he was running for governor and “did not intend to lose.” What initially interested me, however, was that he was a politician from a tiny hamlet in southwest Georgia who nevertheless had a great understanding of the needs of Atlanta, even mass transit. He seemed to be a possible bridge from the historic hostility of rural Georgia, as he spoke forcefully about the environment and his progressive positions on education for all Georgia citizens, black and white. Still, his campaign was a long shot.

Within a few days, he asked to meet again. This time he told me directly that he needed my experience in shaping policies and wanted me to organize and lead a group to provide ideas for his campaign and as governor. I was sold. Sanders had no real interest in me; Carter did. I take no substantial credit for Carter’s victory over Sanders in the all-important Democratic primary and finally in the general election. The group I assembled produced some useful policy papers on education, the environment, and reorganizing and streamlining Georgia’s sprawling bureaucracy. I could hardly imagine that my modest contribution to the campaign would be only the start of more intense work on a national stage that put me at the right hand of the thirty-ninth president of the United States.

During the long presidential campaign I coordinated all of his domestic and foreign-policy positions, and between his nomination and inauguration I was the only staff person who attended CIA briefings with him. During the administration he called on me for advice on a variety of issues outside my field as domestic-policy adviser, including the Middle East peace process. And when he held his first national call-in program from the Oval Office with the television legend Walter Cronkite as moderator, he asked me to sit with him. He took a personal interest in my health, frequently expressing concern that I was working too hard, invited my son Jay to jog with him at Camp David, and Jay, Brian, and Fran to join him in attending the lighting of the first large Hanukkah menorah (supplied by the Chabad-Lubavitch movement) in Lafayette Park, across from the White House. I deeply admired his intellect, his commitment to the public good, and his political courage from the first day I met him in 1969, when he was running for governor, until his last hours in the White House, on January 20, 1981.

INTRODUCTION

Every four years a handful of talented men and women, mainly elected public officials or business leaders, have the audacity, self-confidence, and determination to put themselves and their families through the hell of a presidential campaign in the belief that they are fit to make decisions that affect the lives of hundreds of millions in the United States and billions more people around the world. Their motives are as varied as their personalities, but all are consumed with ambition to accomplish great things. They see the presidency as the way to mark the world with their deepest convictions.

It is conventional wisdom that Jimmy Carter was a weak and hapless president. But I believe that the single term served by the thirty-ninth president of the United States was one of the most consequential in modern history. Far from a failed presidency, he left behind concrete reforms and long-lasting benefits to the people of the United States as well as the international order. He has more than redeemed himself as an admired public figure by his postpresidential role as a diplomatic mediator and election monitor, public health defender, and human rights advocate. Now it is time to redeem his presidency from the lingering memories of double-digit inflation and interest rates, of gasoline lines, as well as the scars left by the national humiliation of American diplomats held hostage by Iranian revolutionaries for more than a year.

Let me be clear: I am not nominating Jimmy Carter for a place on Mount Rushmore. He was not a great president, but he was a good and productive one. He delivered results, many of which were realized only after he left office. He was a man of almost unyielding principle. Yet his greatest virtue was at once his most serious fault for a president in an American democracy of divided powers. The Founding Fathers built our government to advance incrementally through deliberation and compromise. But Carter took on intractable problems with comprehensive solutions while disregarding the political consequences. He could break before he would bend his principles or abandon his personal loyalties.

An extraordinarily gifted political campaigner, he nevertheless believed that politics stopped once he entered the Oval Office and that decisions should be made strictly on their merits. Carter reflected later that it was “a matter of pride with me not to let the political consequences be determinant in making a decision about an issue that was important to the country … because the political consequences are not just whether I am going to get some votes or not, but how much public support I will have for the things I’m trying to do. And I have to say that I was often mistaken about that.”1

To be truly effective, a president cannot make a sharp break between the politics of his campaign and the politics of governing if he wants to nurture an effective national coalition. This Carter not only failed to achieve—he did not want to. Time and again he would say, “Leave the politics to me,” while in fact he disdained politics. He believed that if he only did “the right thing” in his eyes, it would be self-evident to the public,

which would reward him with reelection. However, politics cannot be parked at the Oval Office door, to be brought out only at election time, but must be kept running all the time by cultivating your political base and mobilizing the broader public, its elected representatives, and the interests they speak for, on behalf of clearly defined priorities. They can never be ignored in order to solve problems and to do good. The presidency is inherently a political job: The president is not only commander in chief but politician in chief.

Carter was so determined to confront intractable problems that he came away at times seeming like a public scold—a nanny telling her charges to eat their spinach, for example when he urged Americans to turn down their thermostats to reduce dependence on imported oil. When he summoned outside advisers to Camp David to help him right his ship of state, one young first-term governor from another Southern state advised him: “Mr. President, don’t just preach sacrifice, but that it is an exciting time to be alive.” The advice came from none other than William Jefferson Clinton, the new governor of Arkansas.2 This was not a natural instinct for Carter, who focused more on the obstacles to a better country and safer world than on the rewards that could be enjoyed.

Presidents who leave the White House under a cloud can emerge in the clear with the perspective of history. Who today pays attention to contemporaneous charges that Harry Truman was corrupt and soft on Communism, leaving the White House with an approval rating hovering close to a mere 20 percent, when we now appreciate that he helped construct an international order that lasted for half a century?3 The remarkable domestic legacy of President Lyndon Johnson, on whose White House staff I served, was totally overshadowed by Vietnam—until the fiftieth anniversaries of his landmark bills led to new reflection about his presidency. Bill Clinton, in whose administration I also served, paid a heavy price for a tawdry personal affair. But his significant accomplishments and extraordinary political gifts helped restore him to a position of affection. His immediate predecessor, George H. W. Bush, was dismissed as a silver-spoon president who lost the support of his own party by reversing his commitment never to raise taxes, but it is now evident that he deftly managed the end of the Cold War and avoided the triumphalist trap of chasing Saddam Hussein back into his lair in Baghdad.

President Carter

President Carter